PSYCHOTHERAPY NETWORKER: Let’s start off by talking about your view of addiction. You’ve written that “any passion can become an addiction.” What do you mean by that?

GABOR MATÉ: Addiction is a complex psychophysiological process, but it has a few key components. I’d say that an addiction manifests in any behavior that a person finds temporary pleasure or relief in and therefore craves, suffers negative consequences from, and has trouble giving up. So there’s craving, relief and pleasure in the short term, and negative outcomes in the long term, along with an inability to give it up. That’s what an addiction is. Note that this definition says nothing about substances. While addiction is often to substances, it could be to anything—to religion, to sex, to gambling, to shopping, to eating, to the internet, to relationships, to work, even to extreme sports. The issue with the addiction is not the external activity, but the internal relationship to it. Thus one person’s passion is another’s addiction.

PN: Okay, but the whole subject of addictions is shrouded in a certain amount of controversy these days. What do you think is the most common misconception about addictions?

GM: Well, there are a number of things that people often don’t get. Many believe addictions are either a choice or some inherited disease. It’s neither. An addiction always serves a purpose in people’s lives: it gives comfort, a distraction from pain, a soothing of stress. If you look closely, you’ll always find that the addiction serves a valid purpose. Of course, it doesn’t serve this purpose effectively, but it serves a valid purpose.

PN: Lots of people believe that the term addiction has become too loosely applied. So what’s the difference between saying “I have an addiction” and “I have bad habits that give me short-term satisfaction, but don’t really serve me in the long term?”

GM: The term addiction comes from a Latin word for a form of being enslaved. So if it has negative consequences, if you’ve lost control over it, if you crave it, if it serves a purpose in your life that you don’t otherwise know how to meet, you’ve got an addiction.

PN: Some people are critical of the term addiction because they believe it medicalizes and pathologizes behavior in a way that’s not helpful.

GM: I don’t medicalize addiction. In fact, I’m saying the opposite of what the American Society of Addiction Medicine asserts in defining addiction as a primary brain disorder. In my view, an addiction is an attempt to solve a life problem, usually one involving emotional pain or stress. It arises out of an unresolved life problem that the individual has no positive solution for. Only secondarily does it begin to act like a disease.

[...]

[...]

PN: The notion of trauma is closely tied into your conception of addiction. Why is that?

GM: If you start with the idea that addiction isn’t a primary disease, but an attempt to solve a problem, then you soon come to the question: how did the problem arise? If you say your addiction soothes your emotional pain, then the question arises of where the pain comes from. If the addiction gives you a sense of comfort, how did your discomfort arise? If your addiction gives you a sense of control or power, why do you lack control, agency, and power in your life? If it’s because you lack a meaningful sense of self, well, how did that happen? What happened to you? From there, we have to go to your childhood because that’s where the origins of emotional pain or loss of self or lack of agency most often lie. It’s just a logical, step-by-step inquiry. What’s the problem you’re trying to resolve? And then, how did you develop that problem? And then, what happened to you in childhood that you have this problem?

PN: Some people have challenged your belief that addiction is inevitably connected to trauma. Looking at the research, they say that most addicts weren’t traumatized, and most traumatized people don’t become addicts.

GM: Then they’re not looking at the research. The largest population study concluded that nearly two-thirds of drug-injection use can be tied to abuse and traumatic childhood events. And that’s according to a relatively narrow definition of trauma. I never said that everybody who’s traumatized becomes addicted. But I do say that everybody who becomes addicted was traumatized. It’s an important distinction. Addiction isn’t the only outcome of trauma. If you look at the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, it clearly shows that the more trauma there is, the greater the risk for addiction, exponentially so. Of course, there are traumatized people who don’t become addicts. You know what happens to them? They develop depression or anxiety, or they develop autoimmune disease, or any number of other outcomes. Or if they’re fortunate enough and get enough support in life to overcome the trauma, then they might not develop anything at all.

When I give my talks across the world, it’s not unusual to have somebody stand up and say, “Well, you know, I had a perfectly happy childhood, and I became an addict.” It usually takes me three minutes of a conversation with a person like that to locate trauma in their history by simply asking a few basic questions.

PN: What are they?

GM: Sometimes I ask if either parent drank and I hear, “Yeah, my dad was an alcoholic.” At that point, the whole audience gasps because everybody in the room gets that you can’t have a happy childhood with a father who’s an alcoholic. But the person can’t see that because they dealt with the pain of it all by dissociating and scattering their attention. Maybe they developed ADD or some other problem on the dissociative spectrum. They shut down their emotions, and now they’re no longer in touch with the pain that they would’ve experienced as a child. That’s an obvious one. Less obviously, I might ask about being bullied. And when a person says, “Yeah, I was bullied as a kid”—or just sometimes felt scared, or alone, or in emotional distress as a child—I ask to whom they spoke about such feelings. The answer is almost uniformly “nobody.” And that in itself is traumatic to a sensitive child.

Πηγή: Απόσπασμα από το κείμενο The addict in all of us

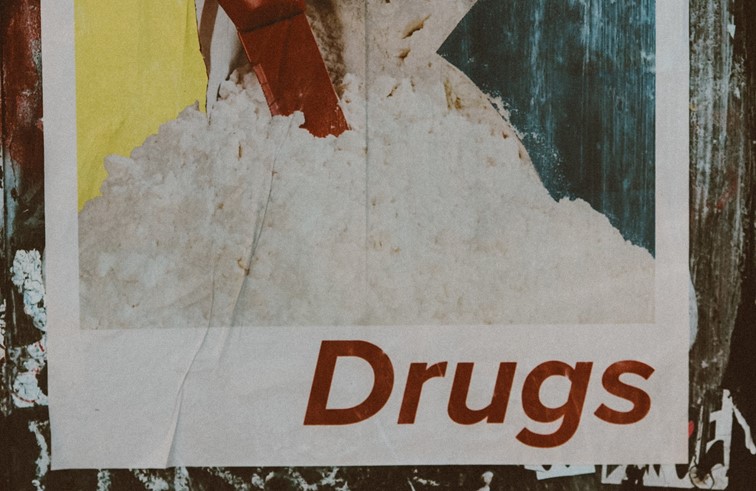

Εικόνα: Jon Tyson

Πηγή: Απόσπασμα από το κείμενο The addict in all of us

Εικόνα: Jon Tyson